CONNECTING LOCAL COMMUNITIES THROUGH RELATIONAL ETHICS OF CARE. THE WORK OF SONIA ROBERTSON1

ARTIGO Edith-Anne Pageot

Edith-Anne Pageot is interested in historiography, the relationship between art and craft, and the interdisciplinary, transcultural, and transnational logic that permeate the modes of production, exhibitions, and reception of art objects. Two major questions underlie and shape her research and serve as a guiding thread for the different bodies of work studied: how to (re)conceptualize the relationships between canons and margins without denying the fractures and their distressing effects? How can we practice an ethically responsible art history based on decentered epistemology to contribute to the development of research and teaching environment aimed at rebuilding the modalities of living together? Edith-Anne Pageot is professor of art history at Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM, Québec, Canada). She is a member of l’Institut de recherche en études féministes (IREF), Centre interdisciplinaire d’études et de recherches autochtones (CIERA), Centre de recherche interuniversitaire sur la littérature et la culture québécoises (CRILCQ). She has published numerous scientific articles and book chapters. She is the author of a monograph on Artistic and media Culture at Manitou College (forthcoming 2002, financed by PAFARC, UQAM, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada). She collaborated in the creation of the first Massive open online course (MOOC), in French, on Aboriginal arts (2022).

RESUMO

Les crises actuelles exacerbent, plus que jamais, la nécessité d’une éthique du care. Pour autant, les discours sur le care ne sont pas nécessairement synonymes de réciprocité et d’émancipation sociale. Le care peut être empreint de paternalisme, reconduire les rapports de pouvoir, ou coïncider avec une forme de bien-être narcissique (self-care) que l’idéologie libérale encourage. À l’opposé, cet article envisage le care à partir d’une perspective relationnelle où l’autonomie n’est pas comprise au sens d’autosuffisance ou d’accomplissement de soi, mais d’interdépendance et d’interconnexions. Il pose l’hypothèse que les approches du care offrent un modèle d’analyse alternatif pour situer des pratiques artistiques transdisciplinaires et ancrées dans des communautés locales. Ce cadre de référence sert à l’analyse du travail de l’artiste Pekuakamiulnu Sonia Robertson (Mashteuiatsh, Québec, Canada). Cet article montre d’une part que les projets de Robertson construits sur la base de liens durables entre des communautés locales, des mondes humains et non-humains est ancré dans une épistémologie ilnue. Des ponts tissés entre des communautés locales issues de différents pays, émergent, d’autre part, une forme de dissidence, une autre façon de « faire monde », façonnée par une éthique relationnelle du care qui résiste au discours hégémonique néolibéral caractérisant les grands évènements en art contemporain « global ».

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Care. Éthique relationnelle. Relations durables. Interconnexion. Autonomie. Local. Global. Sonia Robertson.

Revista Arte ConTexto

REFLEXÃO EM ARTE

ISSN 2318-5538

V.7, Nº17, MAR., ANO 2022

TRABALHO EM ARTE E CUIDADO

Care, Autonomy, and Interconnectedness

Today, more than ever, current crises raise the awareness of the necessity of a relational ethic of care. But what is care? If care can be broadly defined as a relational set of practices and discourses based on attentiveness and a feeling of concern for others, its definition is neither simple nor univocal. Care is not always infused with reciprocity. The discourse of care can be entangled with paternalistic attitudes, empowering those already in a position of power, and thus reinforcing patterns of domination. Care sometimes aligns with victim rhetoric, especially within colonial institutions.

Self-care can be seen as a narcissistic attitude resulting from late capitalism and of neoliberal ideology of wellness, which promotes productivity, independence, and self-sufficiency. This ideology diminishes individuals who do not fit these constructed categories as being “precarious bodies”, “dependent” or “disabled”. (FEDER KITTAY, 2021; SANDELL, 2018) But Judith Butler (2010) reminds us that “precarity” is a by-product of neoliberalism based on two principles: competition and inequality. Thus, precarity and discourses on care, often intertwined, are deeply embedded in social structure and power relationships because of wealth, economic distribution, and political conditions. (BUTLER, 2010, p. 5) It comes to no surprise that under neoliberalism the need for care practises has increased while caretaking institutions have continuously eroded (CLARK MILLER, 2021, p. 48).

Some feminist theorists have pointed out that the sense of caring expected by little girls can sometimes result in a lack of agency and autonomy due to self-denial.

It is not a warm concern for a girl’s projects […] but rather a curbing of her projects as well as her abilities and an instilling of both guilt about others and deep concern for others ‘opinion about her’ – elements of the socialization of females into the feminine role in a patriarchal society. (HOAGLAND, 1991, p. 254)

However, Jean Keller (1997) argues that this interpretation is also based on a Western individualist conception of autonomy associated with self-achievement. Therefore, as she rightly underlies, “the capacity to form and maintain relationships, which has received little attention in the Western philosophical tradition, is arguably just as much of an achievement as autonomy, and just as important for moral maturity.” (KELLER, 1997, p. 154)

As a result, some scholars call for an alternative form of caring. According to Hobart and Kneese (2020), to avoid the pitfalls of patriarchal, colonial, and neoliberal ideologies, care—radical care, per se—needs to be built upon solidarity and mutual aid,

Solidarity […] relies on working with communities and asking them what they need rather than making paternalistic assumptions. Instead of following neoliberal, colonialist development models around innovation and the mining of hope, mutual aid offers space for true collaboration. (HOBART and KNEESE, 2020, p. 143)

The relational ethics of care as a conceptual framework towards assessing community-based art projects?

Keeping in mind that care is understood as a practice which involves interconnectedness2, solidarity, and autonomy defined as the capacity to be in relation, we need to revisit art projects that are deeply interwoven within local communities to understand how these, in turn, shape and outline dynamic and alternative models of progressive and counter hegemonic thinking. In other words, how can the relational ethics of care as a conceptual framework help better assess art practices that are often situated at the crossroads of contemporary art, art therapy and social care organizations that are deeply anchored within the local community? These art practices disturb dominant art history’s norms and global contemporary art logic. There are several illustrations of these types of projects. For example, in Montreal, a non-profit organization founded in 1998 by artists Pierre Allard and Annie Roy called ATSA aims to “advance the cause of sustainable development and the fundamental rights of man and of nature.”3 As well, certain projects by contemporary artist Raphaëlle de Groot involve collaboration with non-profit organizations such as Les Impatients which is devoted to helping people with mental issues through artistic expression and l’Atelier Éclipse which is an artistic enterprise devoted to social inclusion and professional integration. Another example of an art project intertwined with the notion of care is the ongoing collective cartonera project developed in many Latin American cities which produces non-profit handcrafted books by collecting and recycling cardboard from the streets by people who live in extreme “precarity”. Most notably, is the Dulcinéia Catadora, a branch of the cartonera project cofounded by sculptor Lúcia Rosa in São Paulo, Brazil, in 2007.

Sonia Robertson: Pekuakamiulnu4 Artist and Activist

To illustrate how the relational ethics of care as a conceptual framework can assess these connected and relational community-based art projects, I will present an analysis of the work of Pekuakamiulnu artist, Sonia Robertson. An analysis partly nourished by long conversations we have had in 2019. Sonia Robertson lives and works in Mashteuiatsh, a First Nations reserve in the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region of Quebec (Canada). The community of Mashteuiatsh is located on the western shore of the lake, 6 km from Roberval and 450 km north of Montreal. Sedentarization began in the mid-nineteenth century and the Mashteuiatsh reserve was founded in 1856. Before being named Mashteuiatsh, which means “where there is a point”, this region was a passage and summer gathering place where fishing was often successful. Originally known as “Ouiatchouan”, the community has been called Mashteuiatsh since 1985. Among the Ilnu, Piekuakamilnuatsh identify themselves as those who live around Lake Piekuakami. Yet missionaries used to call them “Montagnais” indistinctly, which means, people from the mountains, as they would also rename the great lake “Lac Saint-Jean” in honor of Jean de Quen (1603–1659), the first Jesuit missionary to come in the region.

Besides having a diploma in Interdisciplinary Art (UQC), Sonia also holds a master’s degree in art therapy (UQAT) in which she puts forward the idea that creative activities, culture, spirituality, and holistic healing are deeply intertwined. She explains that “ritual expression and all forms of First Nations art share commonalities with art therapy”. (ROBERTSON, 2027, p. 5. Translated from French by the author) Therefore, it comes as no surprise that her work crosses disciplinary boundaries. Parallel to her contemporary artistic practice, including international in situ projects in Haiti, France, Japan, and Mexico, she is involved in several community initiatives. She is a founding member of innovative local projects which reach beyond the mainstream art contemporary art milieu. For example, in 2001, she co-founded the Sacred Park/Kanatukuliuetsh uapikun in Mashteuiatsh, a community and citizen project with the purpose of safeguarding and transmitting knowledge related to therapeutic plants. It creates a space for the community to develop more autonomy through various social economic projects. (ROBERTSON, 201, p. 51) With, André Lemelin, Sonia cofounded the Atalukan Festival. It is a nomadic festival of myths, tales and legends which tours the neighbouring villages of Mashteuiatsh, Roberval, Saint-Prime, Desbiens, Saint-Gédéon, Alma and Péribonka. Fueled by a strong sense of responsibility and caring, Robertson is also an activist. Notably, she was the Lac-Saint-Jean instigator and spokesperson for the Idle No More protest movement against Bill C-45 which affected 60 acts, including the Indian Act, Navigable Waters Protection act and the Environmental Assessment Act.6

Sonia’s activism and relational approach to art and art therapy, her sensitivity towards local communities, her methodology derived from dreams and immaterial realities are deeply anchored in Ilnu ontology. Traditionally, social organization among Ilnu nomads and semi-nomadic societies was based on relatively small units of related individuals, subdivided into hunting groups, relying on each other, on the territory, and the animal world. The highly decentralized nature of this type of governance made this society an entity whose maintenance was based on the flexibility and the solidity of the family and community ties uniting all the local groups spread over the territory. A resident from Mashteuiatsh explains:

Very strong ideas of autonomy, you just see that in people who are sedentary. […] With nomadic people […] you must move around all the time, so you don’t have the attachment to the ground that is directly below you. I make a difference between land, that’s one thing, and territory, that’s another thing. Territory is a little more abstract concept, it’s a big area whereas land is concrete. (Translated from French by the author. Quoted in ROY, 2015, p. 52)

“Redoing the alliance” collaborative local projects and the importance of interconnectedness

Sonia’s in situ projects foster strong levels of interconnectedness and care for people and the earth and are created in solidarity with local communities through process-based art practices which include modes of knowledge derived from Ilnu’s ontology. As a result of this ontology, living, sleeping, and more importantly dreaming (dreams are considered a message from the spirits) on the site of an artistic project is a recurrent process in Sonia’s artistic practice. In 2002, she installed an altar within the Skol Gallery in Montreal which included a blanket, sacred objects, sage, and tobacco. She insisted on inhabiting the place, alone, at New Year’s Eve. She also “prayed” – rediscovering the ancient ways of praying her ancestors, as she puts it – in the building, “summoning the spirits of the place”.

In 1996, Robertson went to Métabetchouan (about 40 km away from Mashteuiatsh) a part of her ancestral territories where she saw the Jean de Quen statue. From where she stood, she decided to put up her tent and lived on site for a few days. The statue stands on one side of the river where the shore “appears more landscaped with asphalt and a boardwalk”. At that time, she decided to create a project with the idea of “redoing the alliance” between the two sides of the Métabetchouan River and concerns the (re)appropriation of Piekuakamilnuatsh worldviews and modes of communication. As she explained, in Piekuakamilnuatsh ontology, dreaming is a mode of knowledge, of communication and action in the world:

Among Ilnu, if you want to have access to the imaginary world, you must watch the night. […] So, I slept there every day, I made a braid in my hair and then I planted a pole. […] I cut my braids and put them on my poles, but then there was no more pole. I made a circle of my braids in front of the statue of Jean de Quen and I threw the last in the river. (Translated from French by the author. Interview with Sonia Robertson, May 20th, 2019)

In 2018, in Carleton-sur-Mer (Gaspésie, Quebec, Canada), Robertson participated in a creative residency at the Vaste et Vague Artists’ Center where she connected with local communities and collaborated with local artists. (Fig. 1-3) More specifically, she became invested in a tailor-made project for Native teenagers. Inspired by the ancestral know-how of artist Stephen Jerome’s6 baskets, Sonia’s project proposed a reflection on the identity of Mi’kmaq origins in the territory. This resulted in an interactive encounter between groups of women and Francophone and Anglophone students from neighboring schools. As a result, Sonia cocreates in situ installations and reciprocal participative spaces.

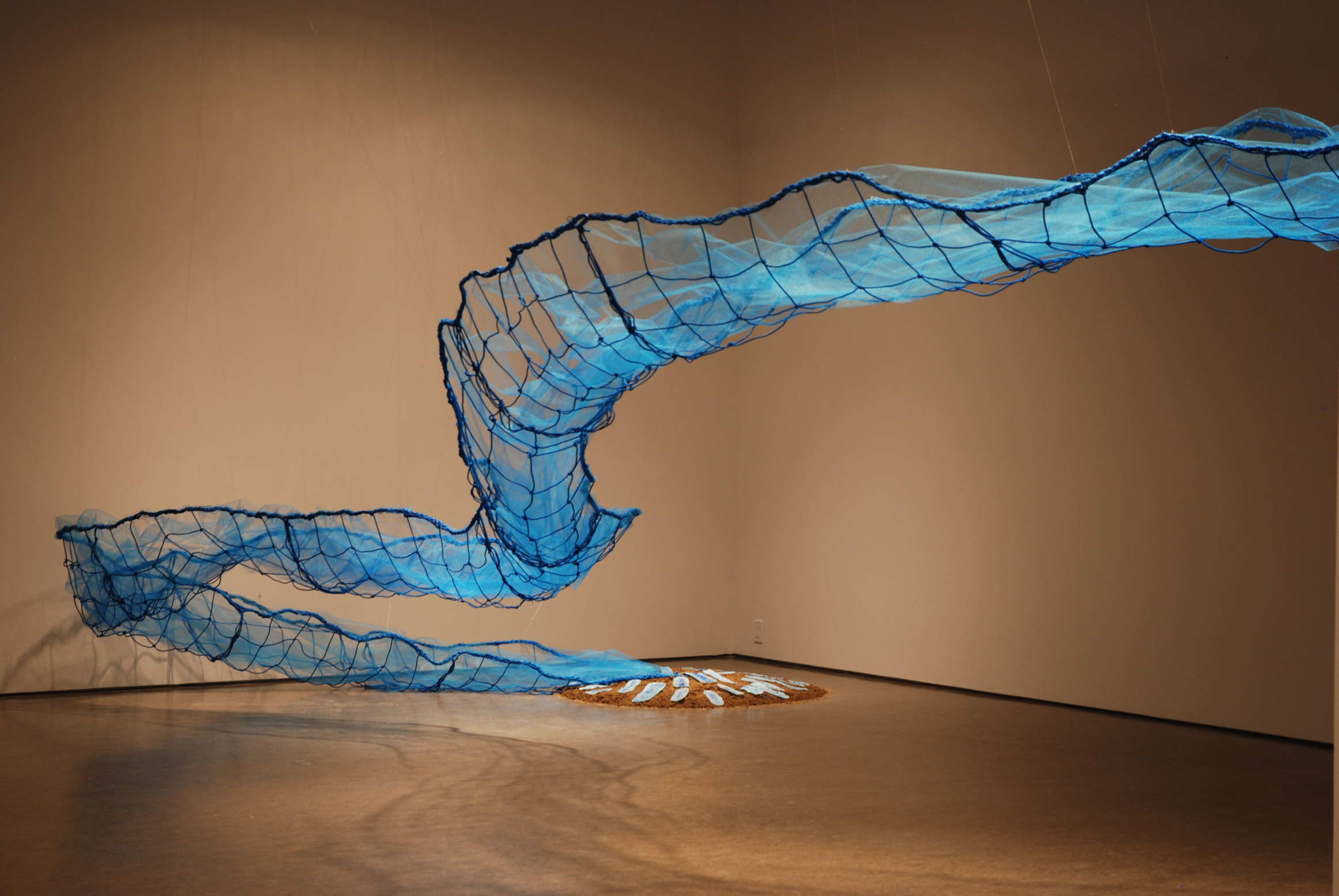

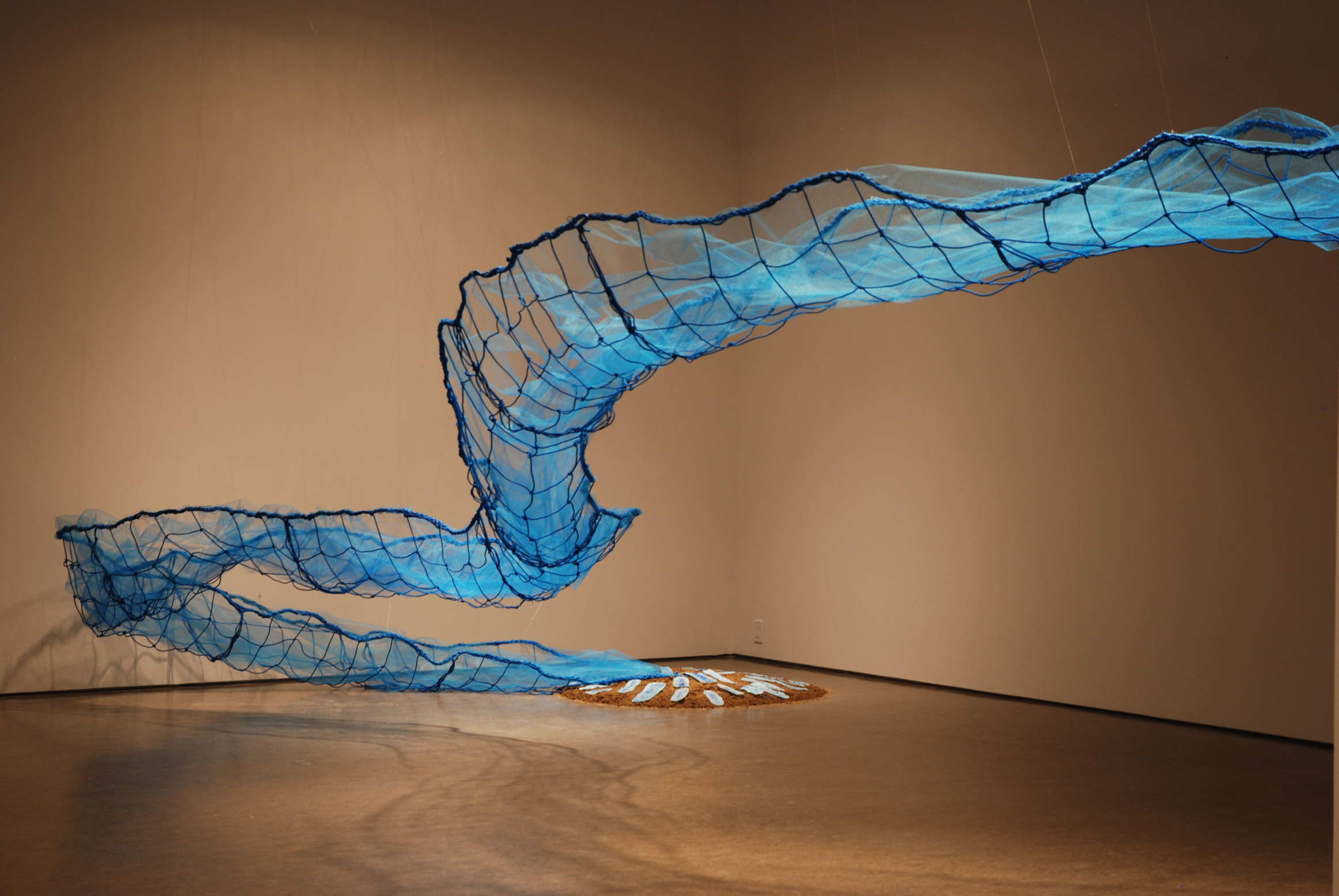

A similar logic forms the basis of Sonia’s Wampum 400 project in Quebec City, a collaboration with Tepehuane-Mexican Canadian artist Domingo Cisneros. In the summer of 2008, at the invitation of curator Guy Sioui Durand, their project was conceived as part of activities reflecting an indigenous critical point of view concerning the 400th anniversary of the foundation of Quebec by Samuel de Champlain. Cisneros and Robertson imagined an immense wampum and a garden in a space strictly circumscribed by a metal fence. Their idea was to, “Redo an alliance which includes the Indigenous people, to demonstrate traditional native know-how and to denounce the past and present situation of Indigenous people.” (Cisneros and Robertson quoted in PAGEOT, 2012, p. 256. Translated from French by the author.) The wampum was made from a collaborative long-term process involving local communities. The plants used to build the wampum were collaboratively collected from their respective territories with the aid of local participants. The careful processes of selecting, collecting, and treating the plants relied on shared knowledge connected to geographical, biological, and local cultural specificities. Furthermore, while participating in the collective exhibition entitled, Nikiwin-Renaissance-Rebirth, Sonia created The Blood of Mother Earth (Le sang de la Terre-Mère, 2014) (Fig. 4) in collaboration with women from the local community of Val d’Or (Quebec). Here is how she relates the genesis of this project:

It was on a Sunday, and I arrived at the Centre, and I saw movement. The next morning, I offered tobacco to the river behind the place where I was sleeping. [She is talking here about the Kânitawigamitek, a tributary of the Ottawa River] The river told me: We should raise people’s awareness of the fragility of the water. So, I started the project with this idea. I let myself be impregnated by this idea. […] I asked the women who came the next day to embroider some words, words of prayers for water.” (Excerpt from the video directed by Catherine Boivin during the exhibition curated by Guy Sioui Durand, Of Tabacco and Sweetgrass: Where Our Dreams Are. Joliette Museum, Feb. 2nd to May 5, 2019. Translated from French by the author.)

As we can see, Sonia’s art practice and creative process is not about representation or metaphors but about inhabiting the world in relation to humans and non-humans, material and the immaterial, anchored within specific spatial environments, local communities, and territories. It is not about explaining the world and exposing knowledge but about caring through embroidering, singing, making basketry, and so forth. In becomes clear that interconnectedness and sustainable relations call for an understanding of autonomy, not based on Western ideology of self-achievement, but infused with a sense of care which concerns the capacity to be in relation, and the capacity to acknowledge our interdependency, and thus our vulnerability, or “precarities” as Butler would put it.

Local/Global

Using the conceptual framework of care, I have focused on artistic projects which are deeply anchored in interconnectedness, stemming from the local, and shaped by relations within a specific geography and community. But commitment to the local also engages critical thinking with respect to the global, more specifically with global contemporary art per se.

Some of Sonia’s projects bridge specific places, modes of knowledge, and sensitivity beyond local borders, thus questioning hegemonic models for international artistic collaboration. In 2013–2014 Sonia Robertson and Guillermina Ortega, (Nashuas) organized a transnational exchange project, Renaissance/Renacer (Fig. 5–6). This project stemmed from Sonia’s participation in the Cumbre Tajin Festival in 2012. It involved three Mexican Indigenous artists, Guillermina Ortega, Santiago Sarmiento et Jun Tiburcio, and three Indigenous artists from Quebec, Sophie Kurtness, Nadia Myre and Sonia Robertson. Robertson explains:

Activities took place and artists were invited to create. There were casas, houses of transmission, weaving, medicinal plants, and ceremonies like the dance of the voladores. We could learn traditional techniques, weaving palm leaves for example, and integrate this knowledge into our works in situ. When they came here, it was a little bit of the same. We visited the cultural transmission site Uashas-sihtsh. Mexican artists were able to witness demonstrations: banana making, fishing nets and pow-wow dances. In addition to the artistic exchange and reflections on art, there has really been a space for sharing our cultures, and our relationship to the world. (Translated from French by the author. Interview with Sonia Robertson, May 20, 2019)

The artists from Mexico stayed in Mastheuiasth during the spring of 2013 and the artists from Quebec stayed in Papantla northern Veracruz, in the de Olarte district the next spring. The project exchange stretched from one equinox to another. Such a long-term framework favoured a sense of continuity, generated a sense of shared spaces, localities, and trust. As a matter of fact, it is through this experience that artist Nadia Myre started to explore the making of nets while considering it as a form of “universal language”. (MYRE quoted in MCLAUGHLIN, 2014)

This exchange project is a sustainable collaborative project built on reciprocity stemming from the local. In that sense, it is the opposite of Nicolas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetic concept which often looks at projects emanating from convivial relationality among an urban elite. The project also is in sharp contrast to the hegemonic global and neoliberal logic of the biennale which “addresses or speaks of the local” (BILBAO, 2019, p. 182) which characterize large contemporary art venues and their objective of global visibility within national frameworks. Rather, it is through an attuned sense of caring and interconnectedness of local communities from different parts of the world that this type of project resists neoliberal global art world and art market discourses. Perhaps the concept of relational ethics of care and the notion of interconnectedness sheds a light on this dissent posture and reveals, at least in part, why this type of local community-based artistic projects, despite their international dimension, have received substantially less scholarly attention than other artists who are based in large cities and participate in the global contemporary art events which provide worldwide exposure.

CONNECTING LOCAL COMMUNITIES THROUGH RELATIONAL ETHICS OF CARE. THE WORK OF SONIA ROBERTSON1

ARTIGO Edith-Anne Pageot

Edith-Anne Pageot is interested in historiography, the relationship between art and craft, and the interdisciplinary, transcultural, and transnational logic that permeate the modes of production, exhibitions, and reception of art objects. Two major questions underlie and shape her research and serve as a guiding thread for the different bodies of work studied: how to (re)conceptualize the relationships between canons and margins without denying the fractures and their distressing effects? How can we practice an ethically responsible art history based on decentered epistemology to contribute to the development of research and teaching environment aimed at rebuilding the modalities of living together? Edith-Anne Pageot is professor of art history at Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM, Québec, Canada). She is a member of l’Institut de recherche en études féministes (IREF), Centre interdisciplinaire d’études et de recherches autochtones (CIERA), Centre de recherche interuniversitaire sur la littérature et la culture québécoises (CRILCQ). She has published numerous scientific articles and book chapters. She is the author of a monograph on Artistic and media Culture at Manitou College (forthcoming 2002, financed by PAFARC, UQAM, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada). She collaborated in the creation of the first Massive open online course (MOOC), in French, on Aboriginal arts (2022).

Revista Arte ConTexto

REFLEXÃO EM ARTE

ISSN 2318-5538

V.7, Nº17, MAR., ANO 2022

TRABALHO EM ARTE E CUIDADO

RÉSUMÉ

Les crises actuelles exacerbent, plus que jamais, la nécessité d’une éthique du care. Pour autant, les discours sur le care ne sont pas nécessairement synonymes de réciprocité et d’émancipation sociale. Le care peut être empreint de paternalisme, reconduire les rapports de pouvoir, ou coïncider avec une forme de bien-être narcissique (self-care) que l’idéologie libérale encourage. À l’opposé, cet article envisage le care à partir d’une perspective relationnelle où l’autonomie n’est pas comprise au sens d’autosuffisance ou d’accomplissement de soi, mais d’interdépendance et d’interconnexions. Il pose l’hypothèse que les approches du care offrent un modèle d’analyse alternatif pour situer des pratiques artistiques transdisciplinaires et ancrées dans des communautés locales. Ce cadre de référence sert à l’analyse du travail de l’artiste Pekuakamiulnu Sonia Robertson (Mashteuiatsh, Québec, Canada). Cet article montre d’une part que les projets de Robertson construits sur la base de liens durables entre des communautés locales, des mondes humains et non-humains est ancré dans une épistémologie ilnue. Des ponts tissés entre des communautés locales issues de différents pays, émergent, d’autre part, une forme de dissidence, une autre façon de « faire monde », façonnée par une éthique relationnelle du care qui résiste au discours hégémonique néolibéral caractérisant les grands évènements en art contemporain « global ».

MOTS-CLÉS

Care. Éthique relationnelle. Relations durables. Interconnexion. Autonomie. Local. Global. Sonia Robertson.

ABSTRACT

The current crises exacerbate, more than ever, the need for an ethic of care. However, discourses on care are not necessarily synonymous with reciprocity and social emancipation. Care can be marked by paternalism, renewed power relations, or coincide with a form of narcissistic well-being (self-care) that today’s liberal ideology encourages. In contrast, this article considers care from a more relational perspective. A perspective in which autonomy is not understood as self-sufficiency or self-fulfillment, but rather of interdependence and interconnections. In fact, care theories may offer an alternative model or framework of analysis for situating transdisciplinary and community-based art practices. A case in point is the analysis of Sonia Robertson’s work, a Pekuakamiulnu artist who resides in Mashteuiatsh, (Quebec, Canada). This article demonstrates that Robertson’s projects are based on sustainable links between local communities and are deeply rooted in Ilnu epistemology using both human and non-human worlds. From these bridges, shaped by a relational ethics of care and built between local communities in different countries, emerges a form of dissidence which resists the neoliberal hegemonic discourse that characterizes major events in ‘global’ contemporary art.

KEYWORDS

Care. Relational ethics. Sustainable relations. Interconnectedness. Autonomy. Local. Global. Sonia Robertson.

Care, Autonomy, and Interconnectedness

Today, more than ever, current crises raise the awareness of the necessity of a relational ethic of care. But what is care? If care can be broadly defined as a relational set of practices and discourses based on attentiveness and a feeling of concern for others, its definition is neither simple nor univocal. Care is not always infused with reciprocity. The discourse of care can be entangled with paternalistic attitudes, empowering those already in a position of power, and thus reinforcing patterns of domination. Care sometimes aligns with victim rhetoric, especially within colonial institutions.

Self-care can be seen as a narcissistic attitude resulting from late capitalism and of neoliberal ideology of wellness, which promotes productivity, independence, and self-sufficiency. This ideology diminishes individuals who do not fit these constructed categories as being “precarious bodies”, “dependent” or “disabled”. (FEDER KITTAY, 2021; SANDELL, 2018) But Judith Butler (2010) reminds us that “precarity” is a by-product of neoliberalism based on two principles: competition and inequality. Thus, precarity and discourses on care, often intertwined, are deeply embedded in social structure and power relationships because of wealth, economic distribution, and political conditions. (BUTLER, 2010, p. 5) It comes to no surprise that under neoliberalism the need for care practises has increased while caretaking institutions have continuously eroded (CLARK MILLER, 2021, p. 48).

Some feminist theorists have pointed out that the sense of caring expected by little girls can sometimes result in a lack of agency and autonomy due to self-denial.

It is not a warm concern for a girl’s projects […] but rather a curbing of her projects as well as her abilities and an instilling of both guilt about others and deep concern for others ‘opinion about her’ – elements of the socialization of females into the feminine role in a patriarchal society. (HOAGLAND, 1991, p. 254)

However, Jean Keller (1997) argues that this interpretation is also based on a Western individualist conception of autonomy associated with self-achievement. Therefore, as she rightly underlies, “the capacity to form and maintain relationships, which has received little attention in the Western philosophical tradition, is arguably just as much of an achievement as autonomy, and just as important for moral maturity.” (KELLER, 1997, p. 154)

As a result, some scholars call for an alternative form of caring. According to Hobart and Kneese (2020), to avoid the pitfalls of patriarchal, colonial, and neoliberal ideologies, care—radical care, per se—needs to be built upon solidarity and mutual aid,

Solidarity […] relies on working with communities and asking them what they need rather than making paternalistic assumptions. Instead of following neoliberal, colonialist development models around innovation and the mining of hope, mutual aid offers space for true collaboration. (HOBART and KNEESE, 2020, p. 143)

The relational ethics of care as a conceptual framework towards assessing community-based art projects?

Keeping in mind that care is understood as a practice which involves interconnectedness2, solidarity, and autonomy defined as the capacity to be in relation, we need to revisit art projects that are deeply interwoven within local communities to understand how these, in turn, shape and outline dynamic and alternative models of progressive and counter hegemonic thinking. In other words, how can the relational ethics of care as a conceptual framework help better assess art practices that are often situated at the crossroads of contemporary art, art therapy and social care organizations that are deeply anchored within the local community? These art practices disturb dominant art history’s norms and global contemporary art logic. There are several illustrations of these types of projects. For example, in Montreal, a non-profit organization founded in 1998 by artists Pierre Allard and Annie Roy called ATSA aims to “advance the cause of sustainable development and the fundamental rights of man and of nature.”3 As well, certain projects by contemporary artist Raphaëlle de Groot involve collaboration with non-profit organizations such as Les Impatients which is devoted to helping people with mental issues through artistic expression and l’Atelier Éclipse which is an artistic enterprise devoted to social inclusion and professional integration. Another example of an art project intertwined with the notion of care is the ongoing collective cartonera project developed in many Latin American cities which produces non-profit handcrafted books by collecting and recycling cardboard from the streets by people who live in extreme “precarity”. Most notably, is the Dulcinéia Catadora, a branch of the cartonera project cofounded by sculptor Lúcia Rosa in São Paulo, Brazil, in 2007.

Sonia Robertson: Pekuakamiulnu4 Artist and Activist

To illustrate how the relational ethics of care as a conceptual framework can assess these connected and relational community-based art projects, I will present an analysis of the work of Pekuakamiulnu artist, Sonia Robertson. An analysis partly nourished by long conversations we have had in 2019. Sonia Robertson lives and works in Mashteuiatsh, a First Nations reserve in the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region of Quebec (Canada). The community of Mashteuiatsh is located on the western shore of the lake, 6 km from Roberval and 450 km north of Montreal. Sedentarization began in the mid-nineteenth century and the Mashteuiatsh reserve was founded in 1856. Before being named Mashteuiatsh, which means “where there is a point”, this region was a passage and summer gathering place where fishing was often successful. Originally known as “Ouiatchouan”, the community has been called Mashteuiatsh since 1985. Among the Ilnu, Piekuakamilnuatsh identify themselves as those who live around Lake Piekuakami. Yet missionaries used to call them “Montagnais” indistinctly, which means, people from the mountains, as they would also rename the great lake “Lac Saint-Jean” in honor of Jean de Quen (1603–1659), the first Jesuit missionary to come in the region.

Besides having a diploma in Interdisciplinary Art (UQC), Sonia also holds a master’s degree in art therapy (UQAT) in which she puts forward the idea that creative activities, culture, spirituality, and holistic healing are deeply intertwined. She explains that “ritual expression and all forms of First Nations art share commonalities with art therapy”. (ROBERTSON, 2027, p. 5. Translated from French by the author) Therefore, it comes as no surprise that her work crosses disciplinary boundaries. Parallel to her contemporary artistic practice, including international in situ projects in Haiti, France, Japan, and Mexico, she is involved in several community initiatives. She is a founding member of innovative local projects which reach beyond the mainstream art contemporary art milieu. For example, in 2001, she co-founded the Sacred Park/Kanatukuliuetsh uapikun in Mashteuiatsh, a community and citizen project with the purpose of safeguarding and transmitting knowledge related to therapeutic plants. It creates a space for the community to develop more autonomy through various social economic projects. (ROBERTSON, 201, p. 51) With, André Lemelin, Sonia cofounded the Atalukan Festival. It is a nomadic festival of myths, tales and legends which tours the neighbouring villages of Mashteuiatsh, Roberval, Saint-Prime, Desbiens, Saint-Gédéon, Alma and Péribonka. Fueled by a strong sense of responsibility and caring, Robertson is also an activist. Notably, she was the Lac-Saint-Jean instigator and spokesperson for the Idle No More protest movement against Bill C-45 which affected 60 acts, including the Indian Act, Navigable Waters Protection act and the Environmental Assessment Act.6

Sonia’s activism and relational approach to art and art therapy, her sensitivity towards local communities, her methodology derived from dreams and immaterial realities are deeply anchored in Ilnu ontology. Traditionally, social organization among Ilnu nomads and semi-nomadic societies was based on relatively small units of related individuals, subdivided into hunting groups, relying on each other, on the territory, and the animal world. The highly decentralized nature of this type of governance made this society an entity whose maintenance was based on the flexibility and the solidity of the family and community ties uniting all the local groups spread over the territory. A resident from Mashteuiatsh explains:

Very strong ideas of autonomy, you just see that in people who are sedentary. […] With nomadic people […] you must move around all the time, so you don’t have the attachment to the ground that is directly below you. I make a difference between land, that’s one thing, and territory, that’s another thing. Territory is a little more abstract concept, it’s a big area whereas land is concrete. (Translated from French by the author. Quoted in ROY, 2015, p. 52)

“Redoing the alliance” collaborative local projects and the importance of interconnectedness

Sonia’s in situ projects foster strong levels of interconnectedness and care for people and the earth and are created in solidarity with local communities through process-based art practices which include modes of knowledge derived from Ilnu’s ontology. As a result of this ontology, living, sleeping, and more importantly dreaming (dreams are considered a message from the spirits) on the site of an artistic project is a recurrent process in Sonia’s artistic practice. In 2002, she installed an altar within the Skol Gallery in Montreal which included a blanket, sacred objects, sage, and tobacco. She insisted on inhabiting the place, alone, at New Year’s Eve. She also “prayed” – rediscovering the ancient ways of praying her ancestors, as she puts it – in the building, “summoning the spirits of the place”.

In 1996, Robertson went to Métabetchouan (about 40 km away from Mashteuiatsh) a part of her ancestral territories where she saw the Jean de Quen statue. From where she stood, she decided to put up her tent and lived on site for a few days. The statue stands on one side of the river where the shore “appears more landscaped with asphalt and a boardwalk”. At that time, she decided to create a project with the idea of “redoing the alliance” between the two sides of the Métabetchouan River and concerns the (re)appropriation of Piekuakamilnuatsh worldviews and modes of communication. As she explained, in Piekuakamilnuatsh ontology, dreaming is a mode of knowledge, of communication and action in the world:

Among Ilnu, if you want to have access to the imaginary world, you must watch the night. […] So, I slept there every day, I made a braid in my hair and then I planted a pole. […] I cut my braids and put them on my poles, but then there was no more pole. I made a circle of my braids in front of the statue of Jean de Quen and I threw the last in the river. (Translated from French by the author. Interview with Sonia Robertson, May 20th, 2019)

In 2018, in Carleton-sur-Mer (Gaspésie, Quebec, Canada), Robertson participated in a creative residency at the Vaste et Vague Artists’ Center where she connected with local communities and collaborated with local artists. (Fig. 1-3) More specifically, she became invested in a tailor-made project for Native teenagers. Inspired by the ancestral know-how of artist Stephen Jerome’s6 baskets, Sonia’s project proposed a reflection on the identity of Mi’kmaq origins in the territory. This resulted in an interactive encounter between groups of women and Francophone and Anglophone students from neighboring schools. As a result, Sonia cocreates in situ installations and reciprocal participative spaces.

A similar logic forms the basis of Sonia’s Wampum 400 project in Quebec City, a collaboration with Tepehuane-Mexican Canadian artist Domingo Cisneros. In the summer of 2008, at the invitation of curator Guy Sioui Durand, their project was conceived as part of activities reflecting an indigenous critical point of view concerning the 400th anniversary of the foundation of Quebec by Samuel de Champlain. Cisneros and Robertson imagined an immense wampum and a garden in a space strictly circumscribed by a metal fence. Their idea was to, “Redo an alliance which includes the Indigenous people, to demonstrate traditional native know-how and to denounce the past and present situation of Indigenous people.” (Cisneros and Robertson quoted in PAGEOT, 2012, p. 256. Translated from French by the author.) The wampum was made from a collaborative long-term process involving local communities. The plants used to build the wampum were collaboratively collected from their respective territories with the aid of local participants. The careful processes of selecting, collecting, and treating the plants relied on shared knowledge connected to geographical, biological, and local cultural specificities. Furthermore, while participating in the collective exhibition entitled, Nikiwin-Renaissance-Rebirth, Sonia created The Blood of Mother Earth (Le sang de la Terre-Mère, 2014) (Fig. 4) in collaboration with women from the local community of Val d’Or (Quebec). Here is how she relates the genesis of this project:

It was on a Sunday, and I arrived at the Centre, and I saw movement. The next morning, I offered tobacco to the river behind the place where I was sleeping. [She is talking here about the Kânitawigamitek, a tributary of the Ottawa River] The river told me: We should raise people’s awareness of the fragility of the water. So, I started the project with this idea. I let myself be impregnated by this idea. […] I asked the women who came the next day to embroider some words, words of prayers for water.” (Excerpt from the video directed by Catherine Boivin during the exhibition curated by Guy Sioui Durand, Of Tabacco and Sweetgrass: Where Our Dreams Are. Joliette Museum, Feb. 2nd to May 5, 2019. Translated from French by the author.)

As we can see, Sonia’s art practice and creative process is not about representation or metaphors but about inhabiting the world in relation to humans and non-humans, material and the immaterial, anchored within specific spatial environments, local communities, and territories. It is not about explaining the world and exposing knowledge but about caring through embroidering, singing, making basketry, and so forth. In becomes clear that interconnectedness and sustainable relations call for an understanding of autonomy, not based on Western ideology of self-achievement, but infused with a sense of care which concerns the capacity to be in relation, and the capacity to acknowledge our interdependency, and thus our vulnerability, or “precarities” as Butler would put it.

Local/Global

Using the conceptual framework of care, I have focused on artistic projects which are deeply anchored in interconnectedness, stemming from the local, and shaped by relations within a specific geography and community. But commitment to the local also engages critical thinking with respect to the global, more specifically with global contemporary art per se.

Some of Sonia’s projects bridge specific places, modes of knowledge, and sensitivity beyond local borders, thus questioning hegemonic models for international artistic collaboration. In 2013–2014 Sonia Robertson and Guillermina Ortega, (Nashuas) organized a transnational exchange project, Renaissance/Renacer (Fig. 5–6). This project stemmed from Sonia’s participation in the Cumbre Tajin Festival in 2012. It involved three Mexican Indigenous artists, Guillermina Ortega, Santiago Sarmiento et Jun Tiburcio, and three Indigenous artists from Quebec, Sophie Kurtness, Nadia Myre and Sonia Robertson. Robertson explains:

Activities took place and artists were invited to create. There were casas, houses of transmission, weaving, medicinal plants, and ceremonies like the dance of the voladores. We could learn traditional techniques, weaving palm leaves for example, and integrate this knowledge into our works in situ. When they came here, it was a little bit of the same. We visited the cultural transmission site Uashas-sihtsh. Mexican artists were able to witness demonstrations: banana making, fishing nets and pow-wow dances. In addition to the artistic exchange and reflections on art, there has really been a space for sharing our cultures, and our relationship to the world. (Translated from French by the author. Interview with Sonia Robertson, May 20, 2019)

The artists from Mexico stayed in Mastheuiasth during the spring of 2013 and the artists from Quebec stayed in Papantla northern Veracruz, in the de Olarte district the next spring. The project exchange stretched from one equinox to another. Such a long-term framework favoured a sense of continuity, generated a sense of shared spaces, localities, and trust. As a matter of fact, it is through this experience that artist Nadia Myre started to explore the making of nets while considering it as a form of “universal language”. (MYRE quoted in MCLAUGHLIN, 2014)

This exchange project is a sustainable collaborative project built on reciprocity stemming from the local. In that sense, it is the opposite of Nicolas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetic concept which often looks at projects emanating from convivial relationality among an urban elite. The project also is in sharp contrast to the hegemonic global and neoliberal logic of the biennale which “addresses or speaks of the local” (BILBAO, 2019, p. 182) which characterize large contemporary art venues and their objective of global visibility within national frameworks. Rather, it is through an attuned sense of caring and interconnectedness of local communities from different parts of the world that this type of project resists neoliberal global art world and art market discourses. Perhaps the concept of relational ethics of care and the notion of interconnectedness sheds a light on this dissent posture and reveals, at least in part, why this type of local community-based artistic projects, despite their international dimension, have received substantially less scholarly attention than other artists who are based in large cities and participate in the global contemporary art events which provide worldwide exposure.

Notas de Rodapé

1 I wish to thank Sonia for her hospitality and generosity in sharing her thoughts with me. This article is a modified version of a conference given at NAASA Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2-6th of October 2019.

2 Furthermore, interconnectedness calls for an understanding of subjectivity which could be described as “singular-plural” (NANCY, 2000), a singular experience of life and death, but at the same time subjectivity framed by relations and processes.

3 https://www.atsa.qc.ca/en/mandate

4 Pekuakamiulnu is the singular form of Pekuakamiulnuatsh. The Pekuakamiulnuatsh are First Nations people who are part of the Innu Nation from Mashteuiatsh. Their language and certain aspects of their culture have local specificities. For example, the spelling of the word Innu (which means “human being”), is written as Ilnu. I have used this spelling in the text.

5 The protest was initiated in November 2012 by four women from Saskatchewan (Canada), Jessica Gordon, Sylvia McAdam, Sheelah McLean and Nina Wilson. The movement quickly spread all over the country.

6 In Gesgapegiag studio, Stephen Jerome continues to manufacture traditional Mi’gmaq traditional black ash baskets. This artistic knowledge is transmitted from Father to Son and has been for several generations.

Notas de Rodapé

1 I wish to thank Sonia for her hospitality and generosity in sharing her thoughts with me. This article is a modified version of a conference given at NAASA Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2-6th of October 2019.

2 Furthermore, interconnectedness calls for an understanding of subjectivity which could be described as “singular-plural” (NANCY, 2000), a singular experience of life and death, but at the same time subjectivity framed by relations and processes.

3 https://www.atsa.qc.ca/en/mandate

4 Pekuakamiulnu is the singular form of Pekuakamiulnuatsh. The Pekuakamiulnuatsh are First Nations people who are part of the Innu Nation from Mashteuiatsh. Their language and certain aspects of their culture have local specificities. For example, the spelling of the word Innu (which means “human being”), is written as Ilnu. I have used this spelling in the text.

5 The protest was initiated in November 2012 by four women from Saskatchewan (Canada), Jessica Gordon, Sylvia McAdam, Sheelah McLean and Nina Wilson. The movement quickly spread all over the country.

6 In Gesgapegiag studio, Stephen Jerome continues to manufacture traditional Mi’gmaq traditional black ash baskets. This artistic knowledge is transmitted from Father to Son and has been for several generations.

Referências Bibliográficas

BILBAO, Ana E. From the global to the local (and back). Third Text, 33 (2), 2019, p. 179–194.

BUTLER, Judith. Frames of war: when is life grievable? London: Verso, 2010.

CLARK MILLER, Sarah. Neoliberalism, moral precarity, and the crisis of care. In: Maurice Hamington, Michael A. Flower. Care ethics in the age of precarity. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2021, p. 48–67.

FEDER KITTAY, Eva. Precarity, precariousness, and disability. In: Maurice Hamington, Michael A. Flower. Care ethics in the age of precarity. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2021, p. 19–47.

HOAGLAND, Sarah Lucia. Some thoughts about caring. In: Claudia Card, Feminist ethics. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1991, p. 246–263.

HOBART, Hi’ilei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani, Tamara KNEESE. Radical care: survival strategies for uncertain times. Social Text, 142, 38 (1 (142)), 2020, p. 1–16. Consulted April 2, 2020.

KELLER, Jean. Autonomy, relationality, and feminist ethics. Hyptia 12 (2), 1997, p. 152–164.

MCLAUGHLIN, Bryne. 4 questions for Sobey Winner Nadia Myre. Canadian Art, December 12, 2014. http://www.nadiamyre.net/press/2014/12/22/canadian-art-feature-december-12-2014.

NANCY, Jean-Luc. Being singular plural. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

PAGEOT, Édith-Anne. Le jardin en ville, le cas des Jardins éphémères à Québec. Stratégie marchande et critique postcoloniale. Globe, Revue internationale d’études québécoises, 15 (1-2), 2012, p. 243–263.

ROBERTSON, Sonia. L’art comme relation à l’imaginaire et espace de guérison. Réflexions autour d’un atelier d’art-thérapie auprès des femmes des Premières Nations de ma communauté – Rêve, imaginaire et femmes sauvages. Essai pour l’obtention de la maîtrise en art-thérapie, Université du Québec Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT), 2017. Unpublished.

ROBERTSON, Sonia. Le parc sacré / Kanatukuliuetsh uapikun. Inter (104), 2009, p. 51.

ROY, Jean-Olivier. Identité et territoire chez les Innus du Québec : regard sur des entretiens (2013-2014). Recherches amérindiennes au Québec 45 (2-3), 2015, p. 47-55.

SANDELL, Richard. Disability: museums and our understanding of difference. In: Simon Knell. The contemporary museum: shaping museums for the global now. London/New York: Routledge, 2018.

Referências Bibliográficas

BILBAO, Ana E. From the global to the local (and back). Third Text, 33 (2), 2019, p. 179–194.

BUTLER, Judith. Frames of war: when is life grievable? London: Verso, 2010.

CLARK MILLER, Sarah. Neoliberalism, moral precarity, and the crisis of care. In: Maurice Hamington, Michael A. Flower. Care ethics in the age of precarity. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2021, p. 48–67.

FEDER KITTAY, Eva. Precarity, precariousness, and disability. In: Maurice Hamington, Michael A. Flower. Care ethics in the age of precarity. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2021, p. 19–47.

HOAGLAND, Sarah Lucia. Some thoughts about caring. In: Claudia Card, Feminist ethics. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1991, p. 246–263.

HOBART, Hi’ilei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani, Tamara KNEESE. Radical care: survival strategies for uncertain times. Social Text, 142, 38 (1 (142)), 2020, p. 1–16. Consulted April 2, 2020.

KELLER, Jean. Autonomy, relationality, and feminist ethics. Hyptia 12 (2), 1997, p. 152–164.

MCLAUGHLIN, Bryne. 4 questions for Sobey Winner Nadia Myre. Canadian Art, December 12, 2014. http://www.nadiamyre.net/press/2014/12/22/canadian-art-feature-december-12-2014.

NANCY, Jean-Luc. Being singular plural. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000.

PAGEOT, Édith-Anne. Le jardin en ville, le cas des Jardins éphémères à Québec. Stratégie marchande et critique postcoloniale. Globe, Revue internationale d’études québécoises, 15 (1-2), 2012, p. 243–263.

ROBERTSON, Sonia. L’art comme relation à l’imaginaire et espace de guérison. Réflexions autour d’un atelier d’art-thérapie auprès des femmes des Premières Nations de ma communauté – Rêve, imaginaire et femmes sauvages. Essai pour l’obtention de la maîtrise en art-thérapie, Université du Québec Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT), 2017. Unpublished.

_____. Le parc sacré / Kanatukuliuetsh uapikun. Inter (104), 2009, p. 51.

ROY, Jean-Olivier. Identité et territoire chez les Innus du Québec : regard sur des entretiens (2013-2014). Recherches amérindiennes au Québec 45 (2-3), 2015, p. 47-55.

SANDELL, Richard. Disability: museums and our understanding of difference. In: Simon Knell. The contemporary museum: shaping museums for the global now. London/New York: Routledge, 2018.

Lista de Imagens

1 – 3 Sonia Robertson Creative residency at the Vaste et Vague Artists’ Center, Gaspésie (Qubec, Canada), 2018, ash and sweet grass. Photo: courtesy of the artist © Sonia Robertson.

4 Sonia Robertson, Le sang de la Terre-Mère, The Blood of Mother Earth, 2014, rope, fabric, sand, paper. Photo: courtesy of the artist. © Sonia Robertson.

5 Sonia Robertson, Renaissance/Renacer, in situ, Mexico, mix media, 2013, corn and plants. Photo: courtesy of the artist. © Sonia Robertson.

6 Sonia Robertson and Sophie Kutness, Renaissance/Renacer, in situ, Mexico, plants 2013. Photo: courtesy of the artists. © Sonia Robertson.

Lista de Imagens

1 – 3 Sonia Robertson Creative residency at the Vaste et Vague Artists’ Center, Gaspésie (Qubec, Canada), 2018, ash and sweet grass. Photo: courtesy of the artist © Sonia Robertson.

4 Sonia Robertson, Le sang de la Terre-Mère, The Blood of Mother Earth, 2014, rope, fabric, sand, paper. Photo: courtesy of the artist. © Sonia Robertson.

5 Sonia Robertson, Renaissance/Renacer, in situ, Mexico, mix media, 2013, corn and plants. Photo: courtesy of the artist. © Sonia Robertson.

6 Sonia Robertson and Sophie Kutness, Renaissance/Renacer, in situ, Mexico, plants 2013. Photo: courtesy of the artists. © Sonia Robertson.